The origin of the name “Lewis Hills” is unknown, but as Jacques Cartier named a nearby headland “Cape Royal”, it likely derives from the name of a French King Louis (e.g., Louis XIII or XIV) whose claim to this coastline dated back to Cartier’s voyage of discovery in 1534. French rule of the coast was officially recognized by the Treaty of Versailles in 1783 when the boundaries of the French Shore were changed to Cape St John on the northeast coast to Cape Ray on the southwest coast. A new detailed chart of the coast was published in 1768 by James Cook who surveyed the region in 1767 after the Seven Years War.

Map at left is from James Cook’s A General Chart of the Island of Newfoundland published in 1775, with Serpentine River named Coal River.

The Lewis Hills are the most southerly of the four Bay of Islands Ophiolite Massifs, and rising to a height of 814 meters (2,671 ft) at the Cabox, they contain the highest point on the island of Newfoundland. They are 24 kms (14 miles) long and 10 kms (6 miles) wide and bounded by Serpentine River in the north, Gulf of St Lawrence in the west, and Fox Island River in the south and east. Road access to the massif is provided by Logger School logging road in the northeast (via the Trans Canada Highway and towns of Mount Moriah and Benoit’s Cove in Humber Arm) and Cold Brook logging road in the southeast (via the town of Stephenville). The IATNL Lewis Hills Trail and UltramaTrex are north to south hiking routes that provide access to the plateau and most of the scenic gulches. Cell phone reception is available at some of the highest elevations such as the Cabox, as well as on the eastern and southern slopes at elevations above the surrounding hills.

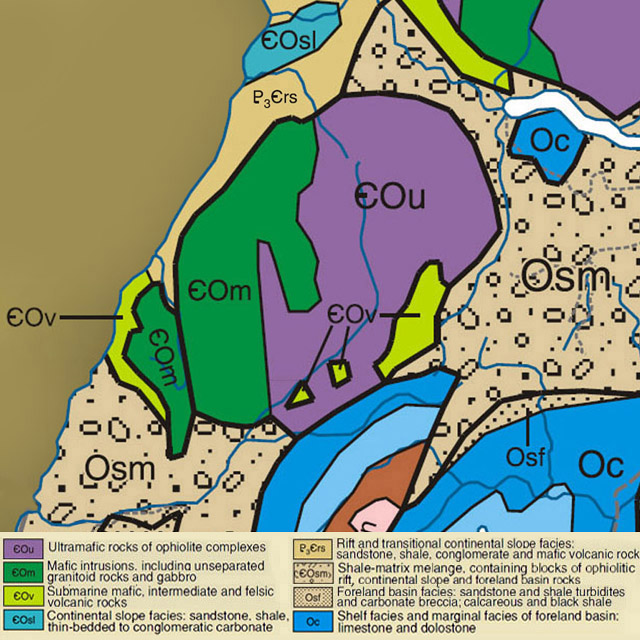

Like the other Bay of Islands Ophiolite Massifs, the Lewis Hills are “broad, ocean-front mesas with enormous alpine tablelands”¹ composed primarily of two distinct geological formations fused together: ultramafic mantle in the east and mafic oceanic crust to the west. The former is characterized by rust-colored peridotite (oxidized when exposed to the elements) and other silicate rock types, while the latter is characterized by gabbro and other intrusive igneous rocks. These formations were forced to the surface by a process of obduction caused by the movement of the earth’s continental plates in a process called plate tectonics. In the 1960’s and 70’s, renowned Newfoundland geologist Harold “Hank” Williams helped confirm this theory by his innovative field work and geological mapping.

The formation of the Lewis Hills spans two geological periods: the Cambrian and Ordovician. The former was the first period of the Paleozoic Era (a time of great geological, climatic and evolutionary change) that began c. 541 million years ago (Mya) with the Cambrian Explosion, when life on earth – primarily in the oceans – rapidly diversified to create representatives of all animal phyla. The Ordovician period followed c. 485 Mya and lasted roughly 41 million years. Life continued to diversify in the ocean, and though dominated by invertebrates such as molluscs and arthropods, vertebrate fish continued to evolve. Over millions of years, the abundant life was transformed into major petroleum and gas reserves. However the Lewis Hills, having been created by igneous and not sedimentary rock, are devoid of both fossils and oil.

The igneous rocks of the Lewis Hills are generally either mafic or ultramafic. The latter are composed of intrusive igneous rock known as peridotite, and include serpentinized harzburgite, dunite, pyroxenite, and lherzolite, while the former are composed of a somewhat more viscous intrusive rock called gabbro that includes diorite and minor trondhjemite. Unlike the other three Bay of Islands ophiolite massifs, the Lewis Hills also contains mafic gneiss, amphibolite, quartz-feldspar gneiss and deformed mafic dykes of the Mount Barren Complex. But like the other three, the Lewis Hills contain some of the best exposures of ophiolitic rock on earth, made all the more visible by the glacier-carved “gulches” that bisect them.

By definition, “ma fic” rocks are high in magnesium and iron (ferrum), while “ultra ma fic” rocks are extremely high in magnesium and iron, to the point they oxidize when exposed to air. As a result, soils composed of these rocks can only support plant species that have adapted to their mineralogical characteristics, including low calcium to magnesium ratio, lack of essential nutrients like nitrogen, potassium and phosphorous, and high concentrations of heavy metals such as iron and chromium. Noteworthy landscapes with endemic species include serpentine barrens at both low and high altitudes, and steep canyon walls with loose scree and low to abundant light.

“The captivating beauty of Lewis Hills … is most evident in the cirques and ravines that adorn the north and south faces. The most eye-catching … and remote of these are the ocean-draining sister-cirques of Molly Ann and Rope Cove Canyons, set facing northwest on either side of Mount Barren. Molly Ann Canyon is a downright Rivendell-esque landscape of waterfalls, rivulets, snowfields, and basaltic cliffs, overlooking the ocean. Rope Cove Canyon, barely a 3 km (1.8 mile) walk across dry tundra to the northeast, could not be more starkly different. … Its headwall is serpentine, its eastern wall is gabbroic, and its western wall is apparently a combination of gabbros and basalts.”²

“There are few other places in eastern North America where such magnificent alpine scenery is juxtaposed so closely with the ocean.” And in spite of the predominantly mafic and ultramafic landscapes, the Lewis Hills massif is a region of rich diversity, supporting “tens of thousands of hectares of boreal, subalpine, alpine and serpentine wilderness.”³ Summer recreation activities on the hills include hiking and camping, with ATVing and hunting popular at lower elevations, and boating and fishing on Serpentine Lake and River. Access by four-wheel drive vehicle is possible most years until snow accumulates some time between mid November and early December.

The coming of snow changes the character of the Lewis Hills dramatically. With the exception of the occasional rock outcrop, the white blanket covers the rust-colored peridotite and grey gabbro, making the unique mineral composition hidden from view. Before long, eager snowmobilers head to the foothills to ride the abundant snow. By late winter, the cycles of rain and snow, mild and cold produces a sufficient base for riders to head into the mountains to explore the valleys and plateaus. For out of town visitors, rentals and/or tours can be arranged.

¹ Beyond Ktaadn, Eastern Alpine Guide, ©2012, p. 183

² Ibid., p. 185

³ Ibid., p. 184-5