Table Mountain Massif is the most northerly of the Bay of Islands Ophiolite Massifs and the only one entirely within the boundaries of Gros Morne National Park. (A small sliver of the North Arm Massif is also within the park boundary.) The source of the name is unknown, though it undoubtedly derives from the broad flat plateau at the summit, which in the east overlooks the South Arm of Bonne Bay. James Cook surveyed the bay and outer coastline in 1767 after the Seven Years War, and in 1783 with the Treaty of Versailles, the entire west coast north of Cape Anguille became part of the French Shore of Newfoundland. Map at left is from James Cook’s A General Chart of the Island of Newfoundland, which shows Bonne Bay, South Arm, Trout River and Green Point, location of the Global Stratotype between the Cambrian and Ordovician geological periods.

Table Mountain, also known as the Tablelands, rises to a height of 720 meters (2,362 ft) and spans an area of approximately 100 square kilometers. It is bounded by Route 431 connecting Woody Point and Trout River in the north, forested foothills and the town of Glenburnie, Birchy Head and Shoal Brook (GBS) in South Arm to the east, Trout River Pond to the south, and the town of Trout River and the coastal mountains of the Little Port Island Arc Complex in the west. It is accessed by Route 431 in the north and east, Trout River Pond in the south, and the town of Trout River from the west. Trail access is provided by Gros Morne National Park’s Tablelands Trail into Winterhouse Brook Gulch in the northeast and the Park’s Trout River Pond Trail near the north shore of Trout River Pond in the southwest. Cell phone reception is limited to the northeast and eastern sides of the mountain, mostly at higher elevations.

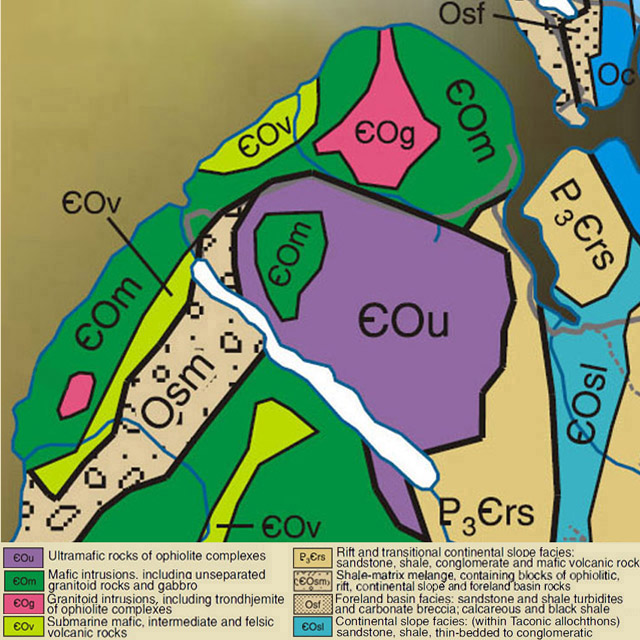

Like the other Bay of Islands Ophiolite Massifs, the Tablelands are “broad, ocean-front mesas with enormous alpine tablelands”¹ composed primarily of two distinct geological formations fused together: ultramafic mantle in the east and mafic oceanic crust to the west. The former is characterized by rust-colored peridotite (oxidized when exposed to the elements) and other silicate rock types, while the latter is characterized by gabbro and other intrusive igneous rocks. These formations were forced to the surface by a process of obduction caused by the movement of the earth’s continental plates in a process called plate tectonics. In the 1960’s and 70’s, renowned Newfoundland geologist Harold “Hank” Williams helped confirm this theory by his innovative field work and geological mapping.

The formation of the Tablelands spans two geological periods: the Cambrian and Ordovician. The former was the first period of the Paleozoic Era (a time of great geological, climatic and evolutionary change) that began c. 541 million years ago (Mya) with the Cambrian Explosion, when life on earth – primarily in the oceans – rapidly diversified to create representatives of all animal phyla. The Ordovician period followed c. 485 Mya and lasted roughly 41 million years. Life continued to diversify in the ocean, and though dominated by invertebrates such as molluscs and arthropods, vertebrate fish continued to evolve. Over millions of years, the abundant life was transformed into major petroleum and gas reserves. However the Tablelands, having been created by igneous and not sedimentary rock, are devoid of both fossils and oil.

The igneous rocks of the Tablelands are generally either mafic or ultramafic. The latter are composed of intrusive igneous rock known as peridotite, and include serpentinized harzburgite, dunite, pyroxenite, and lherzolite, while the former are composed of a somewhat more viscous intrusive rock called gabbro that includes diorite and minor trondhjemite. Like the other three Bay of Islands Ophiolite Massifs, the Tablelands contain some of the best exposures of ophiolitic rock on earth, made all the more visible by the glacier-carved “gulches” that bisect them.

By definition, “ma fic” rocks are high in magnesium and iron (ferrum), while “ultra ma fic” rocks are extremely high in magnesium and iron, to the point they oxidize when exposed to air. As a result, soils composed of these rocks can only support plant species that have adapted to their mineralogical characteristics, including low calcium to magnesium ratio, lack of essential nutrients like nitrogen, potassium and phosphorous, and high concentrations of heavy metals such as iron and chromium. Noteworthy landscapes with endemic species include serpentine barrens at both low and high altitudes, and steep canyon walls with loose scree and low to abundant light.

Table Mountain played an important role in Gros Morne National Park being designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987. The geological field work and mapping by geologists Harold “Hank” Williams and Bob Stevens in the 1960s, 70s and 80s contributed to the understanding of the modern theory of plate tectonics, particularly as it relates to the displacement of oceanic crust and earth’s mantle onto adjacent continental slope. The Tablelands also contain a section of the Mohorovicic Discontinuity, or “Moho,” which is the boundary between crust and mantle generally located between 10 and 12 kilometers below earth’s surface.

According to UNESCO, Gros Morne National Park “illustrates some of the world’s best examples of the process of plate tectonics … and presents the complete portrayal of the geological events that took place when the ancient continental margin of North America was modified by plate movement by emplacement of a large, relocated portion of oceanic crust and ocean floor sediments. … Its rocks collectively present an internationally significant illustration of the process of continental drift along the eastern coast of North America and contribute greatly to the understanding of plate tectonics and the geological evolution of ancient mountain belts.”

Unlike the other Bay of Islands Ophiolite Massifs, snowmobiling is not permitted on the Tablelands, a protected area within Gros Morne National Park. However winter enthusiasts often snowmobile to Southwest Gulch Hut on the east side of the mountain near the community of Glenburnie and ski the foothills around Pic a Tenerife peak. Later in spring, the more adventurous sometimes ski the cirque, or “bowl”, on the north side of the Tablelands to the west of Winterhouse Brook Gulch.

¹ Beyond Ktaadn, Eastern Alpine Guide, ©2012, p. 183